One year later, the school is grappling with a damaged reputation and fractured black community.

Photo courtesy of Anna Moneymaker

THE PERFECT STORM

By Courtney Rozen

May 1, 2018

Taylor Dumpson hasn’t eaten a banana in almost a year.

The smell makes her nauseous.

They trigger memories of her first day as student body president, May 1, 2017, when someone scribbled racist slurs on bananas and hanged them in three spots on American University’s campus. The slurs targeted Dumpson, the school’s first African-American female student body president and her historically African-American sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated. They hurt the school’s broader black community.

“It is something that will forever have an impact on my life,” Dumpson said.

The same day AU confronted a hate crime in Washington, D.C., high school seniors across the country marked the national enrollment deadline and committed to college. Back on campus, students crammed for final exams as Neil Kerwin, the school’s president, marked about one month until retirement. The banana incident thrust the school into the national spotlight. It threatened AU’s past, present and future, making it “the perfect storm,” Dumpson said.

One year later, ten African-American students interviewed for this story said the banana incident tore their already fractured community apart. Even though bad publicity didn’t significantly sway the school’s applicant numbers, that day concerned admissions leaders. As expressions of hate increase on college campuses nationwide, the banana incident forced AU to consider how black students have a different college experience than their white counterparts. Still, no one has been caught for stringing the bananas.

“If it had to be me that this had to happen to for something to get accomplished at this University … then I am happy it was me,” Dumpson said. “But I would not wish the experiences that I’ve had on anyone in the world.”

After marching out of a town hall meeting addressing the banana incident, student protesters hold uppaperwork used to withdraw from the University. Photo courtesy of Anna Moneymaker

‘The world was watching’

With finals week rapidly approaching, students packed Bender Library for all-night study sessions. Two seniors emerged exhausted from the library shortly before 7 a.m.

They noticed a banana, hanged from string tied in the shape of a noose, draped on a lamppost between Mary Graydon Center and the Battelle-Tompkins building. Scrawled on the suspended fruit: hateful and intimidating messages. They called the school’s police department. Fanta Aw, serving as vice president of campus life, later announced that officers found similarly defaced bananas hanged in a total of three spots.

Dumpson only had two things on her mind when she woke up at about 6 a.m. that morning: a mosquito in her bedroom and stomach cramps. She slipped on a shirt with her sorority’s letters and left for campus. As she exited the Metro, a friend sent her a Facebook message with photos of hanging bananas near Anderson Hall.

She dialed Aw. Once she got to campus, Dumpson walked to the bathroom in Mary Graydon Center, locked herself in a stall and called her dad. She couldn’t get her words out through her tears, Dumpson said.

“Don’t let them see you cry,” Dumpson recalls her father telling her. “Don’t let them see you hurt. Keep your head held high.”

Dumpson’s mother didn’t pick up the phone when her daughter called because she was at work. Once she answered, she left the event, jumped in the car and arrived at AU by about 1 p.m. Dumpson’s father drove from Long Island to D.C. in five hours. For days after that, Dumpson’s mother didn’t leave her daughter’s side, Dumpson said.

Dumpson met with Aw for the first time at about noon. Shortly before 1 p.m., Aw announced the banana incident to the entire campus community in an email to students, faculty and staff. About an hour later, Dumpson released her own statement, later cited in media reports.

Solomon Self, student government vice president, left his internship after he saw pictures of the hanging fruit. He spent the rest of the afternoon with Dumpson and members of the incoming and outgoing student government executive boards, including Devontae Torriente, the outgoing student government president.

“If I was in that position, I don’t know how strong I could have been,” Torriente said.

Students later expressed frustration that Aw’s email did not come soon enough. However, Dumpson herself wasn’t fully briefed on the situation until another meeting with Aw at 4 p.m. Students wanted an update before she even knew the full story herself, Dumpson said.

Kerwin released his own statement just before 7 p.m. Monday, announcing a town hall meeting for the next day in Kay Spiritual Life Center. In the hours before he wrote to the campus community, he said he worked with law enforcement to formally classify the banana incident as a hate crime. No day in his 12 years as president was more “disappointing” than May 1, the first day of his final month on the job, Kerwin said.

The “community deserves so much better,” Kerwin said.

Under the Clery Act, universities are required to alert students about threats to their own safety. Kerwin’s memo satisfied Clery Act requirements, so the American University Police Department did not issue an alert itself, said Phillip Morse, assistant vice president of University Police Services and Emergency Management.

“If I made the determination that there was an emergency, that there was an imminent threat of violence, I would make an emergency notification to the community irrelevant of criteria of Clery,” Morse said. “But that didn’t exist.”

Although Dumpson said she didn’t give her first interview until Wednesday, May 3, the banana incident drew national attention from The Washington Post, CNN, ABC News, and others. By that time, #AUSupportsAKA — coupled with statements denouncing the University — had become widespread on students’ Facebook pages.

“It felt like the world was watching,” Torriente said.

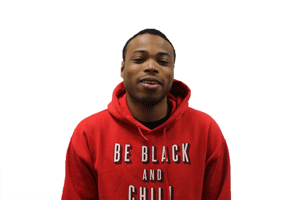

Student protesters block Bender tunnel in hopes their demands would be met by administrators. Photocourtesy of Ted Chaffman

‘We're broken’: Black community divided

That night, black students gathered in The Bridge, the University’s new study space and café. They expressed their frustrations to each other. Then they discussed plans to walk out of the next day’s University-wide town hall in Kay Spiritual Life Center, according to interviews with students who attended the meeting. They’d march to the Asbury Building and demand paperwork to withdraw from AU.

“I never saw so many black students in the same room,” senior Ryan Shepard said.

The campus had been plagued repeatedly by racial incidents in recent years, ranging from a banana flung at an African-American freshman in her dorm to hateful Yik Yak posts. Black students already felt discouraged before the bananas appeared. In a campus-wide survey that closed the day after the bananas were hanged, only 33 percent of African-American students surveyed marked “agree” or “strongly agree” when asked if they feel included on campus, compared to 71 percent of white students.

The bananas were “the straw that broke the camel’s back,” said student protester Helen Abraha.

Click below to hear students’ experiences.

Elizabeth Ogunsuyi

Ma'at Sargeant

Jaha Knight

Ryan Shepard

Lisa Tankeh

Jojo Hamilton

Not only is the black community discouraged by the school’s racial climate, they’re also deeply divided, ten students said. Sophomore Jaha Knight said she spent a lot of her freshman year at nearby Howard University or George Washington University because she saw their black community as stronger.

“The only time when a lot of the black community communicates with each other is when we’re broken,” junior Ma’at Sargeant said.

Different visions on how to move forward from the banana incident emerged that night in the café. The disagreements further splintered an already fractured black community, juniors Othniel Malcolm Andrew Harris and Bryant Bonner said. Dumpson’s election marked a turning point for the black community, Shepard said, which deteriorated on her first day in office.

From the politically savvy, which is how some saw Dumpson, to the more extreme, like Ma’at Sargeant, infighting between black student leaders after the banana incident hurt the community’s ability to achieve progress.

For example, they argued that night about hosting a day party, called a “darty,” on the quad after the planned protest. Students like Sargeant felt it would provide a reprieve for the school’s black community. However, others, including class of 2017 graduate Sydney Young, saw it as insensitive.

Dumpson wasn’t there to debate. Not knowing about the gathering, Dumpson was at the Cheesecake Factory, poking her fork at pasta, when a friend texted her about the meeting. She stopped eating, drove with her mom to campus and walked into The Bridge as the group wrapped up. AKA members didn’t participate in the meeting, Dumpson said.

“I felt as though people were saying, ‘Your voice doesn’t matter,'” Dumpson said.

The next day, students packed Kay Spiritual Life Center for the community-wide town hall. Black students made up seven percent of the school’s undergraduate population that year, according to AU’s 2016-2017 Academic Data Reference Book. Yet Kerwin addressed a town hall crowd of predominantly black students and students of color. Aw, now vice president of campus life and inclusive excellence, described the crowd as “grieving.”

In a recent interview, Kerwin said that beginning in 2014, when the African-American community felt the school was not being aggressive enough with racist incidents like the Yik Yak posts, he began meeting with students, faculty, staff and alumni. He released a five-point diversity and inclusion plan in 2016.

However, Dumpson said the May town hall meeting was the first time she heard Kerwin talk directly to students about race relations. She stood up in the town hall meeting to address Kerwin.

“If you had told me [three years ago] that I would be student government president and that I would have bananas put on my campus … then I would not be at this University,” Dumpson said.

Meanwhile, Alyssa Moncure and Ntebo Maya Mokuena, with the help of Abraha, weaved together a list of demands to pair with the upcoming protest. Their goal was to publish quickly and include as many student ideas as possible, Abraha said. Black student leaders also discussed the demands in a group text message chat, multiple students said. The final list, published on Facebook, was a “hodge podge” of items, Abraha said. It covered a broad range of topics, like educating professors on racism and hiring more faculty and staff of color. It also asked that the University divest from Israel and freeze tuition. Dumpson was not consulted on the list of demands, she said.

About 45 minutes after the town hall began, nearly 100 students walked out of Kay Spiritual Life Center and marched to Asbury. Then they walked back to Kay Spiritual Life Center, where they intended to deliver the list of 14 demands to administrators leading the town hall. However, it had already ended. Instead, Abraha and Moncure took turns reading the list outside the Kogod School of Business on the afternoon of May 2. The Eagle captured it on video.

There was already mistrust in the black community before May 1, Abraha said. After the release of the demands, trust “all ended there,” she said.

Students themselves criticized parts of the list. For example, Young called the demands tone-deaf. Self said that the call to divest from Israel was unrelated. The response from student activists would have been more productive had this not been finals week, Bonner said.

“It looked like we were exploiting this opportunity,” Young said.

Despite opposition, the darty proceeded on the quad after students announced the demands. Dumpson, however, sat in her office in Mary Graydon Center, where she heard music blasting from the quad.

“I felt so alone and isolated,” Dumpson said.

Dumpson hosted her own meeting in Mary Graydon Center on Thursday, May 4. As the focal point of student life on campus, she said she chose MGC so students could not ignore her.

“We wanted it to be the opposite of the town hall from the University,” Kris Schneider, student government secretary, said. “We wanted people to see how the students planned to respond and how we were going to plan to move on.”

After the town hall, Terry Flannery, vice president for communication, led a press conference. University officials handed Dumpson talking points and asked her to stand next to Kerwin, she said, which made her “extremely” uncomfortable. No talking points were provided for Dumpson herself, said Camille Lepre, assistant vice president of communications. Instead, subjects to be discussed by Flannery and Kerwin were shared with her “as a courtesy,” Lepre said, and she was asked to stand near Kerwin at the microphone to speak at the press conference.

Soon after, Dumpson released her own list of action steps — separate from the demands devised by other black student leaders.

The school’s welcome center, where prospective students begin their tour of campus. Photocourtesy of MELANIE MCDANIEL/THE EAGLE

Hate crime didn’t discourage black students from applying for undergraduate admission

At Harlem Village Academy in New York, May 1 marked college decision day. Many of the students would be the first in their families to attend college. Seniors stood on stage, wearing sweatshirts to conceal their college t-shirts, and prepared to reveal their future school to their classmates.

Fatmata Kamara proudly showed off her American University t-shirt. Then, a few teachers approached her, asking if she’d heard about the banana incident at AU. She immediately typed “racial incident” and “American University” into Google.

“It kind of scared me,” she said.

That year, racial tension tainted the school’s admissions cycle from start to finish. As their recruiting cycle opened in September, someone flung a banana peel at an African-American freshman in her dorm.

Eight months later, their year closed with yet another banana-related racial incident. Jeremy Lowe, acting director of undergraduate admissions for 2016-2017 cycle, said that about five students withdrew after submitting their enrollment deposit because of the May banana incident. However, data from the Office of Enrollment shows that the school saw no significant change in the percentage of black applicants for undergraduate admission for the 2017-2018 cycle.

Lowe himself visited KIPP Memphis Collegiate High School in Memphis, Tennessee, to recruit after the September banana incident. The majority of the school’s students are African-American and will be first-generation college students, according to the school’s college adviser, Alexcia Gest. Gest is a graduate of AU’s School of International Service.

Some of her students heard about the banana flung in Anderson Hall from former classmates attending AU, she said. About a dozen of them attended Lowe’s presentation.

“Jeremy was prepared,” Gest said. “He talked about his own feelings regarding the situation and how he feels that AU is going to properly respond to it.”

The admissions office received about 45 phone calls regarding the May banana incident, Ryan Gregor, senior director of enrollment marketing, said. To this day, prospective students and their families rarely ask about about it, multiple student tour guides said. Parents, however, specifically asked about their students’ safety in small-group discussions during orientation the summer after the May banana incident, said Knight, a protester who later became an orientation leader.

“I was concerned that there were going to be people that would say, ‘Forget it, I’m not coming,’” Sharon Alston, vice provost for undergraduate enrollment, said. “That did not happen.”

The admissions team also led a webinar for incoming students and families. Top administrators and two students — Shyheim Snead and Valentina Fernández — spoke to more than 300 people who attended, Lowe said.

For the class entering in the fall of 2005, African-American students applying to AU was less than 7 percent of the total applicant pool. For the freshman class entering in the fall of 2018, the portion was about 9 percent, according to data from the Office of Enrollment.

This year, the school asked undergraduate applicants to define an “inclusive environment” in their application, a change from the previous year.

“We want students to value and appreciate differences,” said Andrea Felder, the school’s new assistant vice provost for undergraduate admissions.

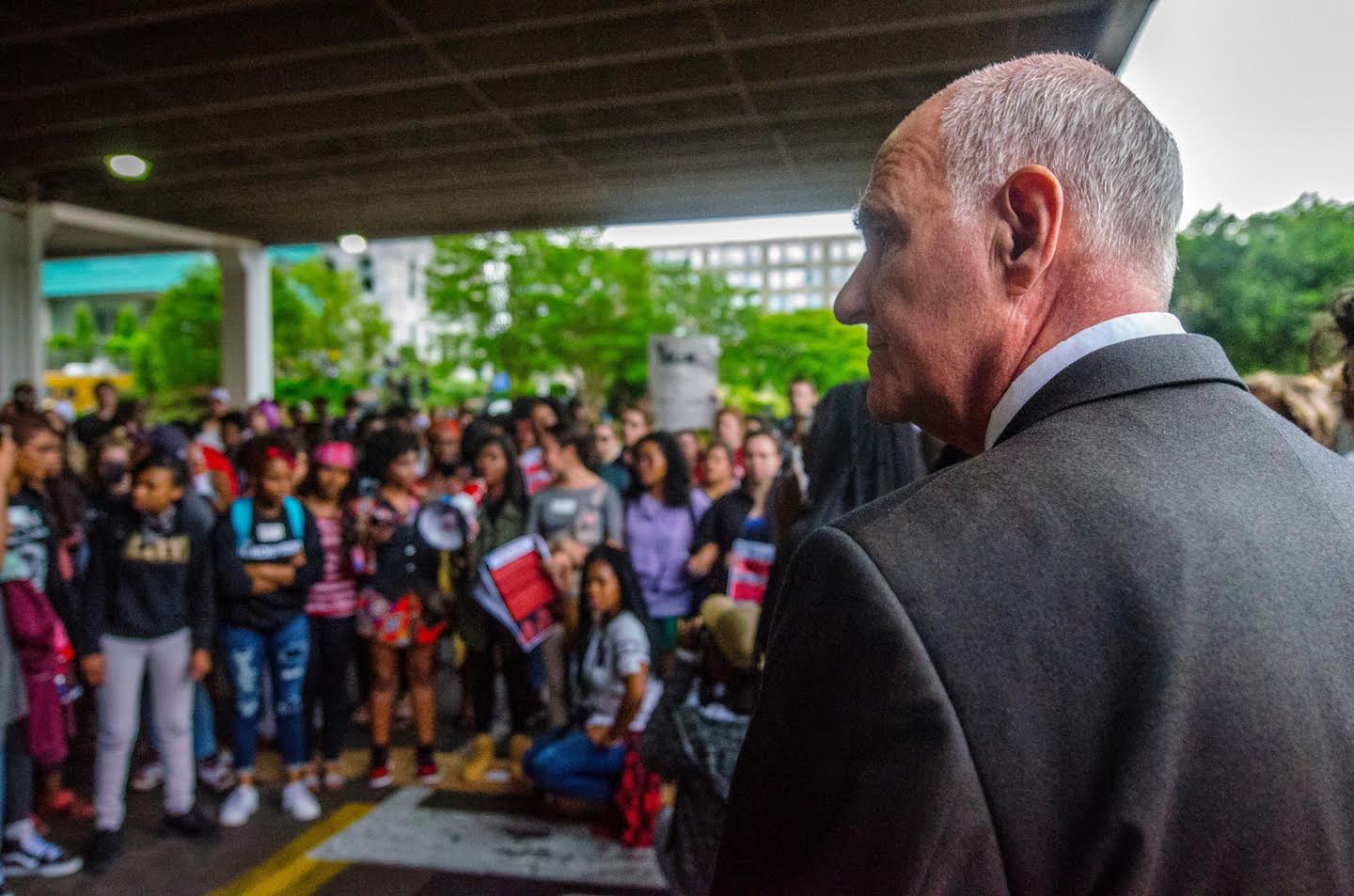

Provost Scott Bass at the #ItsInTheAir protest. Photo courtesy of Ted Chaffman

Frustration prompts second protest

From Sargeant’s perspective, the banana hate crime followed a similar timeline to racial incidents in AU’s past. Student activists protested without making tangible gains. Then they went back to their rooms and others ignored them, she said.

“I felt like I was in … a video game,” Sargeant said. “It’s like the same thing, over and over.”

Multiple students, including Sargeant, Knight, Isaiah Young, Romayit Cherinet and Jasmine Chandler, organized a second protest, called #ItsInTheAir. Students gathered at Katzen Arts Center on Friday, May 5, and then marched through Bender tunnel beginning at 2 p.m. They formed two groups: one to stop traffic in the tunnel and another to block the entrance to the Bender Arena parking garage.

Aw called it a different type of protest than what she’s seen during her decades at AU.

“Call Kerwin!” they chanted while blocking the tunnel and the garage.

The protesters demanded extensions on their final exams, a separate investigative team to probe racism and discrimination at the University, and that The Bridge be designated a sanctuary for students of color for the remainder of the school year.

Knight said they gained traction once staff attempted to exit the parking garage at the end of the school day. A pregnant woman attempted to exit, Knight said. However, protesters wouldn’t move. About 90 minutes after the protest began, Provost Scott Bass arrived. He agreed to the demands and addressed protesters with a megaphone.

“It put me in a good spot as far as getting my voice heard at the table,” Knight said.

Dumpson speaks to University President Neil Kerwin at a town hall following the May banana incident. ANTHONY HOLTEN/THE EAGLE

Hate crime investigation reaches dead end

A year after someone first strung bananas from nooses on campus, the crime is still unsolved. No suspect has been identified and all credible leads have been exhausted, President Sylvia Burwell said in a memo on Friday, April 27.

Local and federal law enforcement officials are collaborating on the investigation, Morse said. AUPD is the lead agency, with the assistance of the U.S. Attorney’s Office, FBI and Metropolitan Police Department. The day after the banana incident, AUPD released two videos depicting a person of interest.

Since then, they haven’t publicly identified a suspect or made an arrest. However, they have consistently briefed Burwell on the investigation and communicated with their federal partner agencies, Morse said.

Despite exhausting all credible leads, the case will stay open, Mark Story, a school spokesperson, said.

Displaying a noose is a crime in D.C. if its intent is to “intimidate,” according to D.C. law. This law applies to the crime at AU because the crime occured in an educational setting and featured nooses displayed in an intimidating manner.

AUPD later classified the banana incident as a hate crime, which allows a court to impose an “enhanced penalty” if the crime is connected to prejudice, Morse said. MPD monitors hate crimes, said Brett Parson, lieutenant of MPD’s Special Liaison Branch.

Kerwin and AUPD later worked with the U.S. Attorney’s Office and FBI to expand the investigation. They designated it a Federal Civil Rights Charge that now includes heavier penalties. Under this charge, the perpetrators, if convicted, could be imprisoned for 10 years, according to U.S. code.

The University also worked with the Anti-Defamation League, an organization which monitors hate incidents nationwide, said Doron Ezickson, the organization’s D.C. regional director. Extremist group activity on college campuses continues to climb, Ezickson said. For example, the ADL counted 147 incidents of white supremacist flyers found on U.S. college campuses during the fall 2017 semester. This marks a 258 percent increase from fall 2016.

Internet access reinvigorated hate groups. However, the rise in online hate activity didn’t translate to in-person action until recently, Ezickson said. White supremacists, for example, have been emboldened by the “political discourse” and are no longer afraid to espouse hate publicly in their communities, Ezickson said.

“We’re seeing a veritable tsunami of hate in our society, and unfortunately, campuses are a major target for that activity,” Ezickson said.

Ezickson has been a key adviser to top AU administrators on combating hate incidents and crimes, he said. On Thursday, May 4, the ADL told AU that Andrew Anglin, founder of a neo-Nazi website, encouraged his followers to troll Dumpson online. The University dispatched campus police officers to protect Dumpson. Flannery, the school’s vice president for communication, announced the trolling in a campus-wide email the morning of Friday, May 5. Nearly one year later, Dumpson filed a complaint in federal court alleging a civil rights violation. One of the defendants is Anglin.

Once the semester ended and students left for the summer, Ezickson trained University administrators and the Board of Trustees in how to combat hate crimes. He advised the University to deny attention to agitators, like those who hang white supremacist posters. Hateful postering is not going away, Ezickson said.

The University’s messaging on this issue appears to follow this advice. For example, Aw, vice president of campus life and inclusive excellence, did not explicitly name the hate group written on anti-Semitic flyers posted on the School of International Service building in February 2017 in her email to the campus community.

“We can define success as having no incidents and be constantly disappointed,” Ezickson said.

A painting made by Dumpson. Courtesy of Taylor Dumpson

‘The girl with the bananas and the nooses’

After the hate crime, Dumpson returned to D.C. to watch her friends graduate. She found herself alone in the district for the first time in a while. In the days after the bananas first appeared, Dumpson was always accompanied by a friend or family member, she said.

“I felt paranoid,” Dumpson said. “I felt like everyone was looking at me.”

She said her identity — which includes her Justice and Law major, Newman Civic Fellow award and student leader — was boiled down to one question from inquisitive parents.

“Are you the girl with the bananas and the nooses?” Dumpson recalls.

Now, Dumpson says she faces post traumatic stress disorder. She’s always hyper-aware of her surroundings and has lost 20 pounds since May 2017, she said.

“She won’t let you see her struggle,” Self said.

In December, she and another AKA member, Kesa White, were suspended from the sorority. The sorority’s national office did not provide a reason for the suspension. In January, Dumpson resigned from her position as president of student government. As of April 2018, the sorority’s AU chapter has one active member, Winter Brooks. She is chapter president. AKA did not add any new members this year, Brooks said. Dumpson would not comment on why she was suspended from the sorority.

As Dumpson prepares to graduate and enter law school, she’s leaving behind a campus tinged by racism. In more than two decades working at AU, Aw said the May banana incident was the “worst” she’s ever seen. Since then, multiple sets of flyers — attacking African-Americans, immigrants and Jews — have been hung on the Northwest D.C. campus. Lisa Tankeh, a member of the school’s NAACP chapter, said that although the banana incident sparked “fire” at the onset, she hasn’t seen substantial change since.

“For the most part, it all kind of just seems like we went on with our lives,” Tankeh said.

Led by Burwell, the school is now implementing a two-year strategy to improve diversity and inclusion on its campus, called the Plan for Inclusive Excellence. Administrators say the strategy will receive $121 million in funding over the course of two years. In addition to other goals, the plan calls for a mandatory discussion-based class for all freshmen. There, students will talk about race, gender and sexual orientation.

The plan will be successful when students can focus on their “holistic education” daily, Aw said, and be able to leave their mark individually on this campus.

“In leaving here, they can say, ‘I mattered as a student,’” Aw said. “That’s very important to me.”

...

Design by Jack Stringer

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Haley Samsel, Chris Young, John Watson, Jennifer LaFleur, Dana Amihere, Tom Fish, American University Television and Sasha Jones for your help with this project.